Fashionable profit-making vs egregious profit maximization.

Navigating the Complexities of Fast Fashion: Lessons from Cambodia

Fast fashion serves as a poignant case study on the boundaries between acceptable profit-making and egregious profit maximization. This industry epitomizes the “race to the bottom”, chasing the cheapest labor while wreaking havoc on our shared planet. During my time in Cambodia, I learned about world of fast fashion, uncovering the harsh realities faced by garment workers and the environmental repercussions of this industry. I continue to be appalled at the idea some people are willing to take advantage of already disadvantaged people. We all live on this planet together, we all get one life… that math will never work for me.

Understanding the Human Cost:

Despite some factories adhering to labor laws and maintaining a degree of compliance, the working conditions remain far from ideal. Workers engage in monotonous tasks day in and day out, with little opportunity for advancement. The gender dynamics are stark; management positions are typically held by men, while the women, who are the backbone and experts of these operations, remain stuck in repetitive roles.

Even in the best-case scenarios where pay and conditions are relatively improved, the lack of career progression and learning opportunities are a constant battle. This systemic stagnation keeps workers in a cycle of perpetual labor without personal growth or development. In addition, the daily commute for many garment workers is a dangerous one, they often pack into overcrowded trucks to reach the factories.

The Fast Fashion Model: Speed Over Substance:

The fast fashion model exacerbates these issues by prioritizing speed and cost over quality and sustainability. Companies like H&M, Zara, and Shein have mastered the art of bringing a product from design to market quickly. This rapid turnover creates enormous waste and puts immense pressure on workers to produce more, faster, and with minimal training. The result? Increased production errors and the loss of bonuses that workers once depended on, leading to further financial instability.

Fast fashion's environmental toll is staggering. The industry produces 92 million tons of waste annually and consumes 79 trillion liters of water, according to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. It’s projected that by 2030, global clothing consumption will increase by 63%, reaching 102 million tons. This model not only generates substantial waste on the retail and production sides but also fails to invest in the workforce, perpetuating a cycle of high pressure and low reward.

Financially, fast fashion giants generate enormous revenue and profit. For instance, Zara's parent company, Inditex, reported revenues of €20.4 billion in 2021 with a net profit of €1.1 billion. H&M generated around $22 billion in revenue, with a profit of $1.1 billion the same year. Meanwhile, Shein, a newer player in the fast fashion arena, reportedly earned $15.7 billion in revenue in 2021, marking a significant rise. These figures starkly contrast with the meager wages earned by garment workers, who often make less than $200 per month, the wealth disparity between fashion executives and the labor force is nearly unfathomable.

Striving for Ethical Production:

In contrast to these destructive practices, some companies are making conscious efforts to operate differently. During my time in Cambodia, I learned about alternative models that focus on sustainability and ethical labor practices. For instance, Tonlé sources fabrics from middlemen who collect and process pre-consumer factory waste, turning it into usable materials, supporting a circular economy.

They companies design collections around readily available materials, ensuring minimal environmental impact. They also use natural dyes, avoiding the harmful chemicals that pollute waterways and endanger communities. For example, traditional dye houses in China have polluted over 70% of the country's waterways, contributing to severe health issues such as cancer in surrounding communities. By using natural, non-toxic dyes, companies can significantly reduce their environmental footprint. This is just one model that demonstrates its possible to produce fashion sustainably and ethically, though it requires a significant shift from the industry norm.

The Path Forward:

My experiences in Cambodia underscored the importance of a multifaceted approach to changing the fashion industry. Activists, governments, companies, and consumers all have roles to play. Activists raise awareness and push for change through protests and public campaigns. Governments can enforce regulations to prevent the import of products made under unacceptable conditions. Companies, especially those with Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives, can take incremental steps towards more ethical practices.

For consumers, the journey begins with education and awareness. Understanding the origins of our clothes and the conditions under which they are made will drive more conscious purchasing decisions. Supporting brands that prioritize ethical and sustainable practices while challenging those that do not is crucial. Ultimately, we need to turn away from a self centered approach to fashion, only asking “how will I look in this outfit?” is simply not enough, but that question must be paired with questions like “where and how was this made?” and “do I need this product?” Every dollar is a vote.

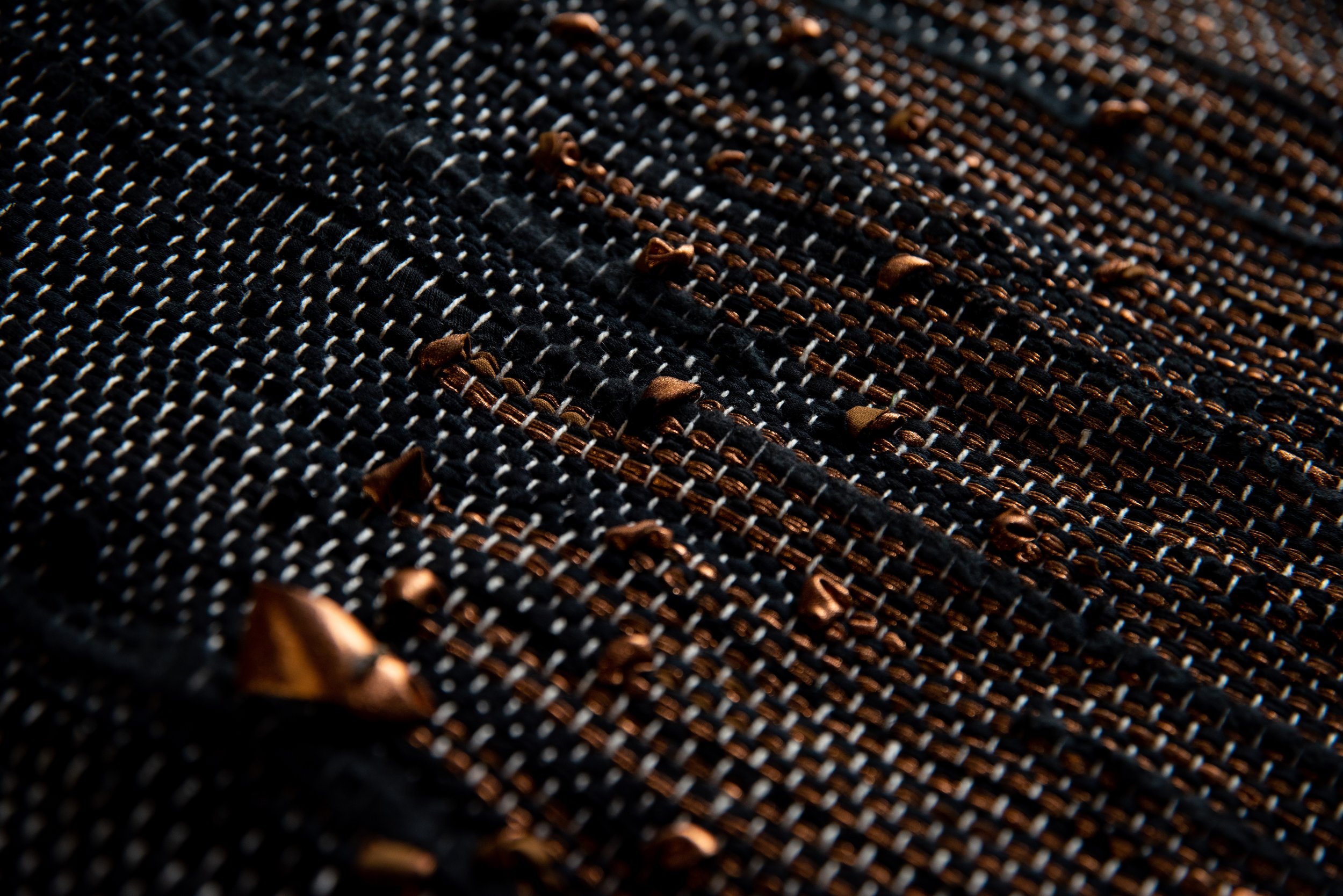

Weaves Cambodia

I traveled to Weaves Cambodia is a weaving facility located in Preah Vihear Province, which specializes in employing individuals affected by landmine accidents. Recognizing the unique needs of their artisans, Weaves Cambodia custom makes looms to accommodate their physical abilities, ensuring an inclusive and supportive working environment. Tonlé sends scraps purchased in the remnant fabric market in Phomn Pehn north to Weaves Cambodia to create new fabrics that otherwise would be wasted. Through their craft, these resilient weavers create beautiful, high-quality textiles!

The Tonle Sap.

Beyond the garment factories, I had the opportunity to explore the unique ecosystem of the Tonle Sap, Southeast Asia's largest freshwater lake. Taking a boat across its expansive waters, I was amazed by the communities living along its shores. These floating villages, with their stilted houses and intricate network of waterways, epitomize resilience and adaptation.

The Tonle Sap is not just a lake; it's a lifeline for millions of Cambodians. It provides sustenance through its abundant fish stocks, supports agriculture with its nutrient-rich floodwaters, and serves as a critical transportation route. The annual flood pulse system, where the lake's size expands and contracts dramatically with the seasons, nurtures one of the world's most productive inland fisheries.

A remarkable feature of the Tonle Sap is its unique hydrological phenomenon. During the wet season, the Tonle Sap River reverses its flow, causing the lake to swell up to six times its dry-season size. This reversal brings a wealth of nutrients from the Mekong River, supporting a diverse array of aquatic life and enriching the surrounding floodplains. This seasonal transformation fosters incredible biodiversity, with the lake hosting over 300 species of fish, numerous bird species, and other wildlife, making it a vital ecological treasure.

However, this vital ecosystem faces threats from overfishing, pollution, and climate change. The communities around Tonle Sap are on the front lines of these challenges, striving to maintain their traditional way of life in the face of mounting pressures.

—

My time in Cambodia was an eye-opening experience that deepened my understanding of the fast fashion industry's complexities and the intertwined fates of its workers and the environment. It highlighted the urgent need for change and the potential pathways to achieving it. By combining ethical business practices with consumer awareness, community support, and regulatory enforcement, we can foster a more sustainable future for fashion and for the communities that depend on the delicate balance of ecosystems like the Tonle Sap.

Fast fashion presents us with a critical question: how far is too far in the pursuit of profit? As we navigate this gray area, it is essential to consider the broader impact of our choices on the environment and on the lives of those who produce our clothing. This moral dilemma challenges us to rethink our approach and strive for a balance that prioritizes both profitability and the well-being of our planet and its inhabitants.

The allure of fast fashion is potent, promising consumers that their clothes will make them look fun, cute, sexy, and appealing. However, this comes at a significant human and environmental cost. While fashion executives amass wealth, earning millions, and living in luxury, garment workers endure harsh conditions and low wages. It's a stark reminder that behind the glossy marketing lies a reality of exploitation and environmental degradation. By questioning our purchasing decisions and supporting ethical brands, we can contribute to a more just and sustainable fashion industry.